Exhibitions and Objects of Wellness—Part 1

Read Time: 11.5 minutes

Associate Professor Brenda Cowan of the department of Exhibition and Experience Design at SUNY/Fashion Institute of Technology (New York) shares her theory and framework for the connection among people, objects and mental health called “Psychotherapeutic Object Dynamics,” in a three-part series for SEGD.org.

Exhibitions and Objects of Wellness: Part 1, A Theory of Psychotherapeutic Object Dynamics

By Brenda Cowan, Associate Professor, department of Exhibition and Experience Design, SUNY/Fashion Institute of Technology

My world is museums and the objects that nestle within them. In exhibitions, objects live and breathe as memories and moments in time. Objects in exhibitions can captivate us and mirror our hopes, our failings, perhaps our better selves. Objects aren’t human, mind you; they just show us over and again that we are. And, the environments in which they nest—that enable and permit us to see ourselves, be ourselves, connect with others and the world around us—are powerful places that can even keep us well.

+++

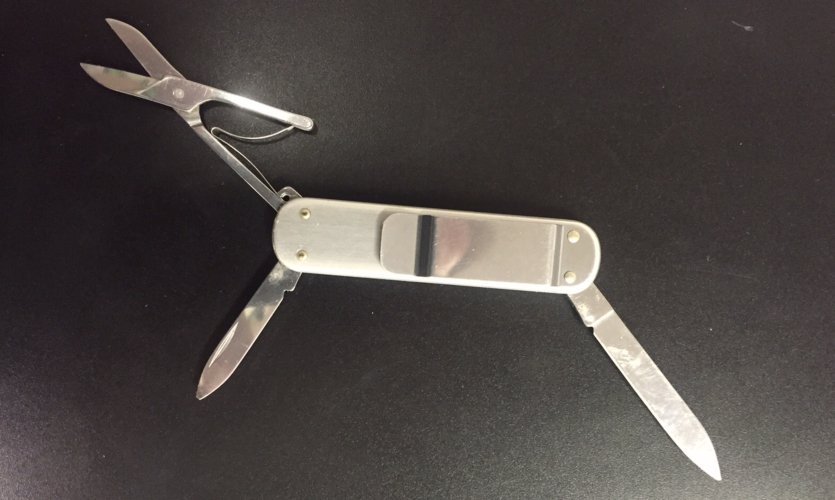

A friend of mine has a snazzy little money clip that his kids gave him over 13 years ago, and in all that time it has rarely left his front shirt pocket. It’s a clever gadget that includes a tiny screwdriver, pair of scissors and a knife (therefore, it’s deemed a weapon by the TSA) forcing him to check his luggage every time he travels. Sometimes, he sends it ahead via Fed-Ex to avoid time apart from it as much as possible. While in the air without the clip, he gets an overwhelming sense of emptiness and imbalance and longs for the feeling of constancy and harmony that comes with having it on him. But why?

Why are objects such an intrinsic part of our lives? Why do we cherish or detest them, protect them or destroy them? Objects live with and around us as our silent life partners, bearing witness, evoking memories and calling us to action. They finish our sentences where words fail us, and they keep us together when we are worlds apart. Try talking with someone about the wedding ring on your finger without touching it. Try picking up the scarf of someone you loved and lost, and not hold it gently, or even search for a scent.

Examining the psychology of the human-object relationship and the impacts of object experiences in exhibitions is my great joy. Much like your average four-year-old, I am fond of asking the why of things, although my whys tend towards interdisciplinary research in object and exhibition studies, phenomenology, psychology and psychotherapy. Areas of scholarship that while complex, if you unpack them, can more or less be summed up in the questions of your average four-year-old: What is that? Why is it here? Where did it come from? What are you doing with it? But, why?

Keenly hidden beneath a professorial guise, my inner four-year-old has been exploring the human-object relationship for years. Through fieldwork in psychotherapy and empirical study in museums, my mission has been to identify and understand the psychological underpinnings of people’s inherent relationships with objects. I’ve followed the premise that people have an innate and necessary relationship with objects that is primary and directly linked to psychological health. Much like our bodies need certain nutrients in order to achieve wellness, our mental health and wellbeing requires object relationships.

I found the key to understanding the healthful impacts of dynamic object engagement through fieldwork in 2015 at Trails Carolina, a therapeutic wilderness facility deep in the forests and foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Sticks, leaves, rocks and other objects found in nature are a critical part of therapeutic treatment at Trails, and through observations and interviews with therapists, field staff and Clinical Director Jason McKeown I was able to see where objects play a role in healing processes.

Following my study at Trails, I visited therapist Ross Laird in British Columbia who also uses objects in his practice. Jason and Ross would later participate in ethical data collection during the museum-based empirical research work, and in grounding the therapeutic elements of my theory and framework for the connection among people, objects and mental health: Psychotherapeutic Object Dynamics.

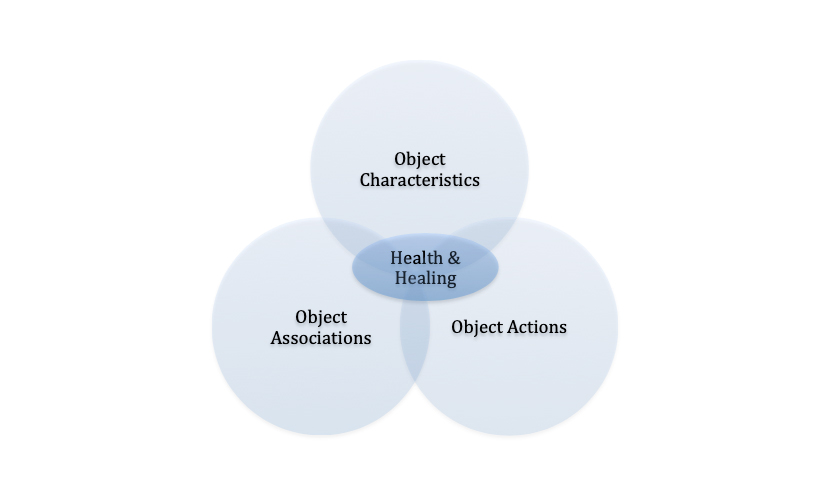

Psychotherapeutic Object Dynamics is grounded in factors of human development as well as the phenomenology of meaning-making experience. It is a psychological mechanism defined by the inherent and inextricable coalescence of subjective object associations, attributed evocative characteristics, and dynamic interactions that result in healthful and healing outcomes. These correlations, interactions and impacts are automatic, self-driven and simultaneous.

So, my friend with the money clip? He subjectively associates the clip with his children and their affectionate relationship. It feels like a connection to his kids and it is a companion in his life. My friend has dynamic experiences with the clip; it was given to him as a gift that he in turn received, and he always keeps it in close physical proximity. The ongoing coalescence of those associations, characteristics and dynamic actions produce outcomes that are therapeutic. With the clip he describes feeling balanced, complete and in harmony. To the TSA, my friend’s money clip is a weapon, but to him it is a means of mental wellness.

But, there are more than two dynamic actions that can be directly linked to healthful outcomes. The Psychotherapeutic Object Dynamics framework is comprised of seven universal forms of object engagement: Associating, Composing, Giving/Receiving, Making, Releasing/Unburdening, Synergizing and Touching. The dynamics are inherent, multidimensional, catalytic, human-object relational experiences, and each is therapeutic in nature. These dynamic experiences occur in everyday life and significantly to us, they also occur in museum exhibitions.

+

Associating is what my friend does with his money clip. It is the action of keeping close to an object in a way that perpetuates its associations and meanings, including experiences, states of being, places and people. The dynamic of associating includes object characteristics such as companion in life experience defined by psychologist Sherry Turkle, and silent partner as defined by cultural anthropologist Silvia Spitta. Associating is demonstrated when an object is consistently kept physically close, whether carried, worn, displayed on a shelf—or even stored away in a box. Feelings of comfort, balance and confidence are integral to the dynamic of associating.

Composing is the action of gathering, collecting or placing two or more objects together in a grouping, where the combination and/or positioning of the objects convey a meaning without words. Composing is at the core of the meaningfulness of creating informal shrines that are seen at the sites where tragedies occurred. It is demonstrated in the labyrinthine composition of sticks and leaves created by the teenager at Trails who couldn’t describe in words how lost and alone she felt. Composing is also demonstrated when someone has a set of objects that is meaningful when every object is arranged in a specific way, such as in a sequence, timeline, or in themes. Whichever the form or composition, this object dynamic is about communicating ideas, emotions or concepts that can only be expressed through objects.

Giving/Receiving, like most of the object dynamics, is deeply rooted in serving the need for human connection. It is a literal transaction that carries meaning, and intentionality. It is experienced when a family heirloom is lovingly given and received through generations, or when a birthday gift is graciously accepted. It is seen to extraordinary affect when a personal object is donated to a museum exhibition where, however humble the object, it is received with reverence and respect. Giving/Receiving is significant to both the giver and the receiver and is the critical human connection that comes when a person opens themselves to another through the giving of an object, and is told through its acceptance yes, I am with you.

Making is the action of creating an object and experiencing the challenges, successes, twists and turns that accompany the process. Ultimately it is about the attainment of goals, achievement, and mastery. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of flow and the experience of heightened creativity are found in the dynamic action of making. It is experienced in different ways: via the activity of making an object and experiencing the creative process first-hand; through observing another person making an object and feeling reverence or awe; or when seeing the marks or physical characteristics of an object’s making on its surface or in its materiality. Exhibitions that show unfinished objects, or objects in the process of being made can have a significant impact on visitors in this way.

Releasing/Unburdening can be seemingly simple, such as the good feeling that comes from a thorough spring cleaning of your home, or when donating your things to a charity. Or, it can be the notable feeling of release that can comes with getting rid of an object associated with a painful memory. Releasing/Unburdening is the deliberate action of permanently removing an object from your life in order to feel a sense of freedom, relief, or distance from its meaning. We seek to make change via this dynamic action. An object can be a burden and its associations and characteristics can inhibit personal growth and the ability to make necessary change. With Releasing/Unburdening, the object has a meaning that can feel bigger than the person, and through removing—even destroying—the object a person can move on with their lives, can maintain wellness, or heal through a trauma.

Synergizing is based on the action of contributing an object to a larger collection of objects. It is when we seek to join with something larger than ourselves, and through participation in an object-based group action, become a part of a collective meaning or message. Psychologists Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Eugene Rochberg-Halton’s theory of the cosmic self—a transactional experience where a person seeks interconnection with others in order to achieve feelings of harmony—is related to the concept of synergizing. Synergizing underscores the success of participatory museums and co-created exhibitions, and results in deepened prosocial behavior, compassion and empathy.

Touching is an action that occurs when a person is consciously or subconsciously engaging with an object’s meaning. As with each of the Psychotherapeutic Object Dynamics, touching is a seemingly simple action that is nonetheless quite complex. The dynamic of touching can occur during the literal act of touching an object with a receptor in the skin (touching is not dependent upon hands), and can also occur when thinking of, anticipating, or remembering touching an object. The memory of tactile and haptic object experiences, what psychologists Gallace and Spence call tactile memory, can elicit feelings of nostalgia, comfort and connection, even as much as being in the moment of touching an object.

+

Empirical evidence of the Psychotherapeutic Object Dynamics in museum exhibitions—which will be featured in Part 2 of this series—shows the remarkable healthful affects of object encounters in passive object-based exhibitions, in highly interactive object-based exhibitions, and in participatory museum experiences where people can engage with curation, restoration and personal object donation. I will share the journey of the empirical research phase and how all seven dynamics were found alive and kicking in each of four, highly differentiated museums that partnered in the testing: the National September 11 Memorial and Museum in New York; the War Childhood Museum in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina; the Derby Museum and Art Gallery in Derby, England; and the Museum at FIT in New York.

These studies also revealed the ways in which object relationships are universal and bond humans in ways that transcend culture, age and life experience: throughout the studies, an elderly woman from the Caribbean shared the exact same beliefs about her objects as did a young man from Korea; a Syrian refugee emotionally reflected on her grandmother’s objects in the exact same way that a woman of privilege in New York did; a man from Africa saw his kin in an object just like a 9/11 first responder saw his family in an object of his own. Psychotherapeutic Object Dynamics has provided a lens for seeing exhibitions, objects, health and human connection in a new way.

But there’s more that we can do with the theory: I’ve adapted the framework as an instrument for evaluating the healthful and healing impacts of exhibitions, and recently used the tool to identify the outcomes of an exhibition co-created by Syrian refugees and Sweden’s Museums of World Culture. This application and overview of the study in Sweden will be the focus of a third and final article to come.

+++

I’ve found that when presenting my work, either formally or when speaking with friends and colleagues, I can rarely go through all seven object dynamics without being interrupted by an enthusiastic “My best friend’s coffee mug is just like that!” Or “Wait, let me show you my lucky stone!” I’ll hear, “I remember when I burned those socks just to get him out of my life,” and “I can’t wait until my daughter is old enough for me to give her my collection.”

I will inevitably be taken away by stories of visits to exhibitions where an object moved someone to tears, or prompted them to take action on something that they had been uncertain about; stories that have reminded them of a person they thought they’d forgotten, or a place they once new. The tangents are endless and at this point, expected—and it’s wonderful.

References

- www.psychotherapeuticobjectdynamics.com

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly and Eugene Rochberg-Halton. 1981. The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1990. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, Inc.

- Gallace and Spence. 2008. “A Memory of Touch: The Cognitive Psychology of Tactile Memory.” In H.J. Chatterjee, ed., Touch in Museums: Policy and Practice in Object Handling. Oxford: Berg. 163-182

- Spitta, Silvia. 2009. Misplaced Objects: Migrating Cultures and Recollections in Europe and the Americas. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Turkle, Sherry. 2007. Evocative Objects: Things We Think With. Cambridge, MA and London: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.