“Sustainable Design”

Partner Content

As someone whose career revolves around making site-specific installations for built environments, a thought has been haunting me for the past few years: Experience Design is inherently unsustainable. In any way they are done, honestly. Interactive experiences are more often than not pseudo-permanent late-stage prototypes that are expected to work like bespoke polished products. These experiences have unrealistic demands to be bold and different from existing work but are to be developed in a predictable fashion: the work must be eye-catching and emotionally engaging while remaining familiar and undemanding; and the technology should be at the cutting edge of research, but also stable and predictable. There are inherently unsustainable misalignments across the spectrum of Experience Design, from concept to user experience to development.

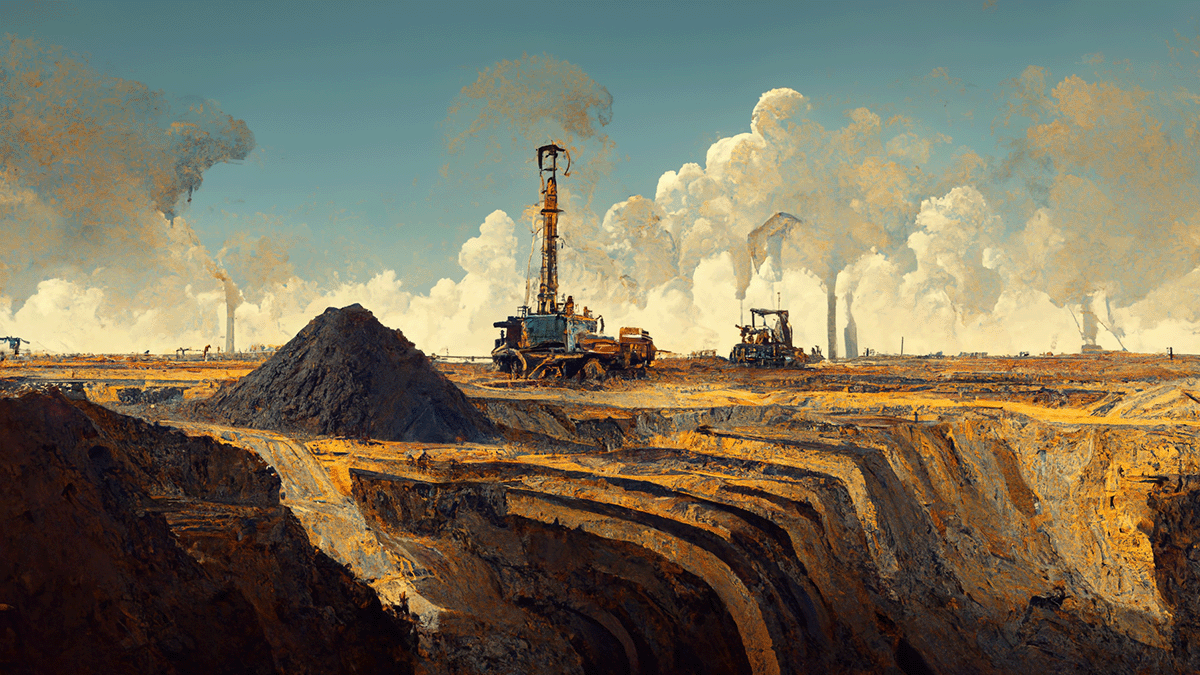

Speaking of unsustainability, another significant area of misalignment is our relationship with sustainability itself. The natural world is a huge inspiration to many of us, and there’s an uncountable number of amazing projects that use the natural world as visual and conceptual metaphors. Unfortunately, these projects are completed in a manner of unawareness – while we’re inspired by the natural world, the work itself is terrible for it.

The built environment is one of the largest producers of carbon emissions in the world as-is, and incorporating technology as a building material will only increase the burden. The modern technologies we rely on require mining rare natural resources from the earth through energy-intensive processes. Converting these materials into electronics through processes that produce terrible chemical wastes furthers this damage. The virgin materials for technology are being extracted at a faster rate than they can be replenished; a number of important materials like copper and lithium are expected to be at risk by 2050.

With such a huge environmental impact, it’s remarkable that some of these projects are about sustainability itself – whether they’re projects meant to showcase the sustainability efforts of a client, promote sustainability amongst citizens, or just celebrate the beauty of nature itself. There’s a contradiction to our work using technological forms as a metaphor for sustainable behavior, when the creation process is itself unsustainable.

So what are some ways in which we can make our work more sustainable? I’ve been focusing on big wins for the last year, and here’s some thoughts on what I’ve found.

Circular Economies

Most people I’ve spoken to tend to equate an equipment’s carbon footprint with how much power it consumes. But for computers and display technology, more than half of the footprint is embodied in the manufacturing process – the mining and processing of material, manufacturing the equipment, and the packaging and shipping related to distribution. What’s even more distressing is that these figures are only true if the equipment is properly disassembled, recycled, and reused! If it’s just thrown into the junk heap, then the carbon footprint from manufacturing easily eclipses the rest of it.

The only real solution around this is to use fewer electronics, and make sure that they’re recycled properly. You may ask – how the heck am I supposed to use less equipment and still get my work done? And the answer relies on focusing on quality over quantity.

We need to shift away from the mindset of doing things the cheapest way possible, and to the most efficient way possible. That means focusing on things that are built to last, built to be repaired, and built to be recycled. Often the cheapest products cut costs ruthlessly and don’t plan for the full lifecycle of the product – so that means we need to avoid the allure of cheap stuff and stick to higher quality products that will last longer, be more easily repairable, and can be disassembled into different materials and recycled.

We need to shift away from the mindset of doing things the cheapest way possible, and to the most efficient way possible. That means focusing on things that are built to last, built to be repaired, and built to be recycled.

Wrapping your head around all of this requires an awful lot of research that most of us don’t have the time for, so I’ve been leaning on the TCO-Certified product listings to do the work for me. While some organizations focus on just the carbon footprint, TCO is looking at the entire lifecycle of products from where their raw materials come from to how the manufacturer supports end-of-life. An increasing number of manufacturers, like Dell and Lenovo, are also making information about the full lifecycle footprint of their products easier to access.

Maintenance and End-Of-Life

No one likes to think about the end-of-life, but every project has an ending. Even “permanent” installations rarely last beyond 10-15 years before the technology and designs start feeling dated, which inevitably leads to a refresh of a space. For marketing and branding projects the lifecycle can be dramatically shorter – from weeks to months.

Even the best laid plans go awry, so it’s important not just to source sustainable equipment, but to be there to make sure that retirement goes as planned.

Countless times I’ve seen clients not know what to do with pieces of technology when they’re done with it and simply junk it – or sometimes just store it in a warehouse indefinitely because they don’t know how to deal with it!

A lot of design companies find the maintenance and support phase of their work exhausting – it’s less exciting than creating something new, and often involves dealing with lots of nuisance issues – but continued engagement is really the only way to make sure that your plan gets followed. This is something that we’re experimenting with at my studio; to be frank, we haven’t had projects up long enough to have had to worry about this yet. For all new projects we’ve started bundling the end-of-life costs into the project fees so that our clients and partners are essentially “pre-paying” for ethical disposal, as an incentive to call us back when they’re ready to move on from the project. We’ve also been working on a client-by-client basis to figure out how to stay involved to help properly support our installations in a way that’s economical for everyone involved.

…we’ve started bundling the end-of-life costs into the project fees so that our clients and partners are essentially “pre-paying” for ethical disposal, as an incentive to call us back when they’re ready to move on from the project.

Sustainable Process

For the past few years, our studio has been tracking the carbon footprint of individual projects as well as our overall practice (I could write another post entirely dedicated to this, reach out if you want to know more!). One of our major findings was that shipping is a leading source of carbon emissions in a project – oftentimes 2x-3x the actual energy consumption! On one project, I saw a computer (653 kg CO2e footprint) get shipped by air round-trip to another country at the cost of 1.1 tons of CO2e. It would’ve been better for the environment to just buy a second computer!

And this scales across your entire project. Every time you pick “Next Day Air” to rush that one crucial part, it’s going to be transported by air – the most carbon-intensive way to ship something. It’s even worse if, in your rush, you order the wrong thing and have to order a replacement (also by air), or buy three new parts to jury-rig a solution from what you have on-hand.

The solution here is to avoid the rush entirely – avoiding the just-in-time, last-minute culture is crucial to minimizing the impact that our installations are having. As an added benefit, avoiding that kind of last-minute culture also reduces your stress levels!

Circular and Sustainable Design

Lately, I’ve been focusing on how to take these ideas about sustainability and apply them early on in the design process, instead of just in the production of our work.

One way I’ve done this is to set energy goals for the design itself. I’m currently working with a client to refresh an installation I helped create a decade ago. It has over 20 displays and 8 computers running it, and we wanted to refresh the content so that it felt less dated and reflect changes to the institution. We decided that as a part of this work, we’d only update equipment if the energy savings justified the energy cost. In some cases, energy savings can justify new equipment – modern computers run faster, require less cooling, and render more pixels with a single graphics card than they could 10 years ago. And in other cases, the energy savings aren’t there – once we consider the cost of manufacturing, replacing the old displays with newer ones would still put us at a net deficit in energy.

Giving ourselves an energy “budget” to play with – in this case, the existing one – has been an irreplaceable tool in guiding our decisions. In future projects I’m hoping to be able to develop what our budget is early on and design from that point forward.

In other projects, we’re looking to avoid screens entirely. Screens have become so common – we see them in city squares, in building lobbies, mounted on walls within our homes, even in our pockets – I can’t help but wonder how much we’ve become unphased by them. Are there better ways to catch people’s attention and engage them emotionally than simply throwing more pixels at the problem?

We’ve been challenging ourselves to think more creatively in future designs; we’re actually working on a new proposal at the moment that uses motors, shutters, and dichroic glass to shape the ambient light in a space. We’re hoping that thinking along these lines won’t just create works that are more in line with our sustainability goals, but that can be more eye-catching, thought-provoking, and engaging in new ways.

About Sitara Systems

At Sitara Systems, we aim to create interactive works that challenge audiences to think critically about the future so that they can help shape it. We take ideas about complex systems and break them down into easy-to-digest pieces; we provide opportunities to reflect on the things that are important to us, and we create experiences that give audiences a sense of wonder and inspire them to do more. While we’re experts in technology and design, our work takes us across a variety of domains. What we bring to each project is a way of thinking about the world.

About Nathan Lachenmyer

Nathan Lachenmyer is a human-computer interaction researcher whose work investigates the changing relationship between humans and emerging technologies, and how technology can be used as a tool to communicate and inspire people. He is a Partner at Sitara Systems, a technology and design laboratory that works with artists, museums, and brands to communicate their messaging and expertise to the public through interactive experiences.

People also viewed

-

Sitara Systems To Refresh Hospital’s Zebrafish Display With NFC Technology

Sitara Systems To Refresh Hospital’s Zebrafish Display With NFC Technology